French Impressionism In The Heart Of Paris

It's safe to say that for many of us, when we think of the centuries of art that have served to fix Paris as the cultural capital of Europe, what comes to mind above all else, perhaps even the soaring towers of Notre Dame and the Place de la Concorde's gold capped obelisk, is the work of the French Impressionists. Manifesting a sense of urban bustle that is unexpectedly punctuated by moments of aesthetic sublimity, it is no wonder that these painters of light have come to define a collective and indelible visual representation of the City of Light's true vibrancy.

The term impressionism began as a critical slight leveled at artists such as William Turner and John Constable, whose atmospheric compositions were often dismissed by academicians as unrefined daubing. In 1872, however, Claude Monet (1840-1926) attempted reclamation of the insult by titling his seminal portrayal of the English Channel at sunrise Impression, Soleil Levant. While the designation remained, it is interesting to note that the artists we now group together as the Impressionists did not emerge in the later decades of the nineteenth century as a movement united by a singular manifesto. Rather, they became aligned by the influence of Edouard Manet (1832-1883), whose stark rejection of Romanticism's nostalgic tendencies became the wellspring of modern painting. Through highly individualized approaches the Impressionists sought to convey a reflection of the truly contemporary, achieved by embracing their immediate surroundings and emphasizing visual resonance over intellectual inference.

Often credited as the fathers of what has become characteristic Impressionist technique, Camille Pissarro (1831-1903) and Alfred Sisley (1839-1899) began experimenting with plein-air painting, forgoing endless studio revision for on-the-spot interpretations of the transient effects of sunlight on the landscape. While Sisley's paintings often capture light with a masterfully calculated clarity, Pissarro's more fluid depictions of Parisian gardens and Montmartre's wide boulevard, rendered in feathery brushstrokes and riotous color, have become nearly synonymous with our notion of Impressionism.

Whereas Pissarro and Sisley favored broad vantages and vistas, the work of Pierre-Auguste Renoir (1841-1919) and Edgar Degas (1834-1917) reflects a more embedded perspective. Renoir's sun-dappled parks and outdoor cafes often appear to overflow with joyful crowds of Parisians, successfully conveying the tension between observation and inherent participation that is unique to life in the city. Degas, as well, is often preoccupied with crowds, but uses their energy to explore movement and gesture. Even his more stoic portraits, exemplified by the iconic L'absinthe, tend to be filtered through idiosyncratic perspectives (a technique undoubtedly influenced by the advent of photography) that force the viewer into the scene.

As the effects of light, atmosphere and movement became increasingly dominant in the work of these artists, the subject, for the first time in the history of Western art, began to approach irrelevancy, an idea that would become the dominating agenda of Modernist practice for years to come. Of all the Impressionists, it was Claude Monet (1840-1926) who was most willing to explore the subjugation of the object for the sake of visual perception. In 1877 he began a series of paintings depicting the Gare Saint-Lazare, one of Paris' busiest railway stations. What sets these works apart from his earlier paintings, and perhaps those canvases produced during his later years at Giverny, is Monet's increased attention to the light as refracted through both the station's glass ceiling and the billowing steam from the locomotives, thereby transforming the very symbol of the industrialized age, the engine, into pure color.

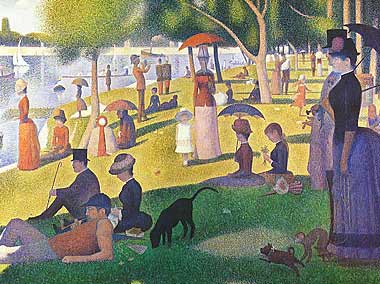

While Impressionism enjoyed sustained support in America into the first decade of the twentieth century, in France it began to fade with the development of new ideas, such as the highly calculated color theory of George Seurat (1859-1891), and new perspectives, as evidenced in the eerily nocturnal world of Henri de Toulouse-Lautrec. Still, one of the world's most impressive collections of Impressionist painting remains in Paris at the Musee d'Orsay, housed in a stunningly refurbished beaux arts train terminal along the Seine, and a visit to the museum is essential to any stay in the city.

Source: http://www.articlecircle.com/ - Free Articles Directory

About the Author: M. Davies is a contributing writer for Welcome2France, a rental service offering corporate housing in Paris as well as an authority on outsider art .

|