|

The Ancient Modernist: El Greco

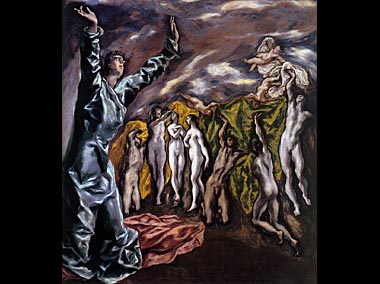

El Greco’s The Opening of the Fifth Seal is utterly stupendous, it is staggering, it really is. I find it baffling that this piece of art was created in the early years of the seventeenth century, the curious figure of St. John is so contemporary, like a modern mystic. It leaves the viewer so curious as to where El Greco derived this vision of the Book of Revelation account about the persecuted receiving salvation. However, it is a puzzle which can be unravelled, for it is not a case of El Greco being like the modernists, rather it is the modernists being like El Greco. The movement, colours, symbolism and emotion of his work has influenced painters for centuries but yet not in El Greco’s own time. He was too much a maverick, he was completely ignored, indeed most viewed him disdainfully. Like many of his paintings which were painted over, El Greco was exiled to the furthest rim of the artistic pantheon, a shadowy, dower character. He lingered there for some time, before the Romantics of the late 1700s realised his genius and raised him to the most elevated of ranks.

Strangely, El Greco now had a clatter of friends, no more was he on his lonesome, as artists two hundred years his junior were gazing back and following his direction. This scenario leaves people scratching their heads, the oddity of El Greco, stuck in time, trying to get back to the future. Some have theorised that he was astigmatic, that he actually perceived people in such elongated forms, but this much too simplistic a theory and does not explain all the rest of his innovations - the colours, the forms, the vision. Some have being base enough to deduce they are a product of the hallucinogenic ravings of a pothead, and so by extension an effortless endeavour? I very much doubt it. This is a screaming soul, heaving out his individuality, his is the most intense of self expressions. Never losing sight of his vision led him to be a prototype for so many movements, while modern giants like Cezanne, Picasso and Pollock all hailed his greatness.

Of course El Greco had to possess influences, he did not just appear with paintbrush in hand frantically seeking canvases to splash. His overriding influence was the Byzantine style of Titian and by extension Tintoretto and Bassano. Later moving to Rome, he was inspired by the legacy of Raphael and Michelangelo. Although, he verbally dismissed the latter as someone who had no idea how to paint, Michelangelo’s influence can most certainly be seen in his work, indeed he contributed massively to a re-evaluation of that particular artists work.

However, El Greco was primarily moulded by the clashing of cultures and fusions of civilisations. He was born on the island of Crete, at a time when it had become a lonely, exposed outpost of Christendom in the Ottoman dominated eastern Mediterranean. And yet, it wasn’t as simple for the Greek Orthodox citizens of the island to look West, they had been under the draconian law of Venice, Byzantium was their original centre but the Turks now controlled that city leaving the Cretans feeling very vulnerable. The belligerent threat of the Ottomans eventually encouraged the Cretans and Venetians to bond, resulting in a blending of their cultures and traditions. El Greco trained in such a Crete as an icon painter, merging Byzantine traditions and Venetian trends. He re-located to Venice, where he studied the Venetian Renaissance developments in colour and perspective. He continued his itinerant wanderings, ending up in a Rome in which thousands of Spaniards were flooding into, because of the growing alliance between the Italian states and the empire of Phillip II. El Greco was moving in intellectual circles that championed the values of the Counter-Reformation and Renaissance humanism which blended antiquity with contemporary trends. In 1576, he made his way to Madrid, most likely seeking the patronage of Phillip II to work on the great basilica of El Escorial. However his plan never materialised, he failed to win any royal commissions. Isolated and abandoned, he snatched at the offer of a commission in the much maligned and declining backwater of Toledo.

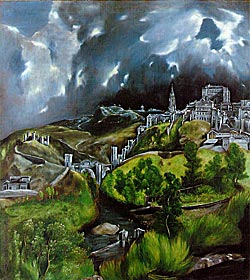

However, Toledo was where the genius of El Greco emerged. All his influences, travels and experiences combined to mould him into the most original of artists. He perfected his unique style of broodingly dark colours, quixotic figures, elongated forms and curiously lit vistas. It was this very singularity that ensured El Greco remained on the fringes but it was also what ensured his immortality. During his own lifetime, he was criticised for his complex iconography and anti-naturalist style. However, at the beginning of the twentieth century Delacroix and Manet latched onto the expressiveness and bold colours of his work. The Symbolists drew on his cold strokes and the asceticism of his figures while Picasso studied the multi-directed expressions of light and ravelling of space and form, proclaiming El Greco to be the first Cubist.

Russell Shortt is a travel consultant with Exploring Ireland, the leading specialists in customised, private escorted tours, escorted coach tours and independent self drive tours of Ireland. Article source Russell Shortt, http://www.exploringireland.net/escorted-tours-page.html http://www.visitscotlandtours.com/tours/escorted-tours.html

|

|

| |

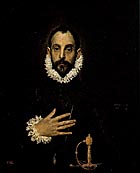

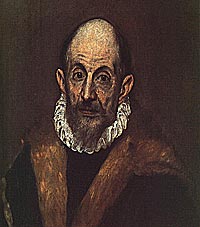

One of the most remarkable Spanish artists, b. in Crete, between 1545 and 1550; d. at Toledo, 7 April, 1614. On 15 Nov., 1570, the miniature-painter Giulio Clovio wrote to Cardinal N. Farnese, recommending El Greco to his patron, describing him as a Cretan, who was then in Rome and had been a pupil of Titian. El Greco, however, derived very little influence from his master, for his works, beyond a certain influence of Bassano, Baroccio, Veronese, or Tintoretto, are individual and distinct. El Greco came to Spain in 1577. He signed his name in Greek characters, using the Latin form of his Christian name, and repeatedly declaring himself as a native of Crete. He appeared before the tribunal of the Inquisition at Toledo in 1582, as interpreter for one of his compatriots who was accused of being a Moor; he then definitely announced that he had settled in Toledo. Nothing is known of his parentage or early history, nor why he went to Spain; but in time he became typically Spanish, and his paintings exhibit all the characteristics of the people amongst whom he resided. From very early days he struck out a definite line for himself, glorying in cold tones with blue, in the use of grey and many varied tones of white, and in impressionistic work which foreshadowed ideas in art that were introduced one hundred and fifty years later. His first authenticated portrait is that of his patron and fellow-countryman, Clovio, now at Naples; his last, that of a cardinal, in the National Gallery. His first important commission in Spain was to paint the reredos of the Church of Santo Domingo of Diego at Toledo. He may have been drawn to Spain in connexion with the work in the Escorial, but he made Toledo his home. The house where he lived is now a museum of his works, saved to Spain by one of her nobles.

His earliest important work is "El Espolio", which adorns the high altar in Toledo, but by far his greatest painting is the famous "Burial of the Count of Orgaz" in the Church of Santo Tomé. The line of portraits in the rear of the burial scene represents with infinite skill almost every phase of the Spanish character, while one or two of the faces in the immediate background have seldom, if ever, been equalled in beauty. It is one of the masterpieces of the world. The influence of El Greco in the world of art was for a long time lost sight of, but it was very real, and very far-reaching. Velasquez owed much to him, and, in modern days, Sargent attributes his skill as an arist to a profound study of El Greco's works. El Greco's separate portraits are marvels of discernment; few men have exhibited the complexities of mental emotion with equal success. The largest collection of his works outside of Spain belongs to the King of Rumania, some of the paintings being at Sinaia, others in Bukarest. In the National Gallery of London, in the collections of Sir John Sterling-Maxwell, the Countess of Yarborough, and Sir Frederick Cook, in the galleries of Dresden, Parma, and Naples, and in the possession of several eminent French collectors are fine examples of his work. But to study El Greco's work to perfection one must visit Toledo, Illescas, Madrid, the Escorial, and many of the private collections of Spain, and his extraordinary work will be found worthy of the closest study. He was a man of eccentric habits and ideas, of tremendous determination, extraordinary reticence, and extreme devoutness. He was a constant attendant at the sacraments, made complete arrangements for his funeral before he died, and was buried in the Church of Santo Tomé.

COSSIO, Memoir of El Greco (3 vols., Madrid, 1908); BARRES AND LAFOND, Domenico Theotocopuli (Paris, 1911).

GEORGE CHARLES WILLIAMSON.

Catholic Encyclopedia

|

| |

|

This store brought to you by |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|