|

The Birdman, Artist in Disguise - Max Ernst.

Max Ernst performs task of the artist perfectly - he transports. The viewer is plucked from reality and deposited in a parallel universe which is distorted, beautiful, awful, great and terrible. It always appeared that it was going to be this way, for even the young Max tested axioms - he confused humans and birds, supposedly not being capable of really telling the difference. Nor did he stop with these ‘simple’ confusions, pretty soon he was strolling around his hometown of Brühl proclaiming himself as Jesus Christ. I think we can safely take it, that the young Max was into the business of myth creation. His father helped in these crafty delusions, literally painting Max as the Messiah, contributing to the moulding of a boy of wonder. And if that wasn’t enough, young Max felt the touch of the ghost of the magician Agrippa as he wandered around Cologne poring over the theological works of Magnus, he who claimed to have created an android in the thirteenth century. It was an auspicious youth, capped by avid study of Freud’s Interpretation of Dreams. But perhaps that would have being that, perhaps when Ernst entered the machine of work and graft, he would have complied with the world. Instead he was ripped from his slumbering cocoon and flung into the terrifying trenches and hell of World War One.

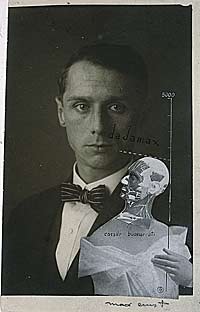

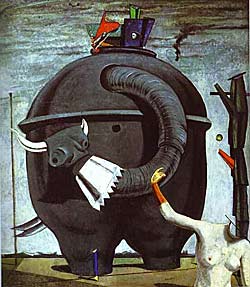

Without this horror, he may have been alone, but there was now a generation of subversive intellectuals who were not going to take the swill being fed by the machine. Together they railed against traditional views of culture, arts and literature. Together they created Dada, attempting to deconstruct the maxims of logic and reason which had led the world into almost annihilating itself amidst the devastation of the First World War. Their collective psyche produced a dreamlike imagery of bizarre juxtapositions and the mixing of unrelated realities. Ernst’s most famous work of this early period was The Elephant Celebes, the curiously alluring mechanical elephant. Even now it stands out, it’s still odd, back in the 1920s, it must have been like the definition of insanity itself. Signing it as Dadamax, Ernst was the zeitgeist, it would be far from the last time, beyond having his finger firmly on the pulse, Max was to go beyond, becoming a soothsayer, warning Europe of the ominous tracks that it was hurtling itself carelessly down.

From an early age, he had set out his stall to be a painter; studying the early German masters in his local Cologne, reading Freud and Nietzche and hanging with the burgeoning artistic set in the Rhineland. He set his sights on Paris, and then World War One got in the way, devastating Europe and killing many of his friends in the process. Ernst still would not budge from his destiny, surviving the trenches in France and Poland, whilst still managing to paint, even exhibiting in Berlin in 1916. He stuck to his goal, but it was completely changed, he now needed to hack into the civilisation that had created hell on earth. He turned from the world, entering his subconscious, rejecting realistic stimulation; attempting to reach a super reality, formed by uncontrollable desires and urges.

The collage was a process that suited his thinking perfectly - objects randomly selected and then arranged to create a whole form. Ernst juxtaposed polarised objects, creating disturbing yet compelling forms, thus creating new meanings and interpretations of these images. From collage, Ernst invented frottage (pencil rubbings on paper or canvas) and grattage (scraping pigment from canvases). Max had never sought artistic credibility or merit, Dada was in fact seeking the exact opposite. So as the unwanted spotlight began to blind him, he burrowed deeper and deeper into his subconscious, embarking on the Sisyphean task of creating art to destroy art. Of course it was an impossible task, Ernst achieved the opposite, his collage paved the way for a new aesthetic of brilliance that would be influential, very influential. His collages were different, they established a coherence and were, bizarre as this may sound - plausible. Paradoxically, Ernst was blending the conscious and the unconscious, the artistic and the non-artistic so to speak. In such a process, all origins of the separate elements are concealed; submerged by the whole, becoming the whole.

His imagination had gone far beyond Paris when he moved there in 1922. Successfully combining the techniques of painting, assemblage and collage on a large scale, he produced the disturbing masterpieces - Oedipus Rex (1922), Teetering Woman (1923) and Two Children are Threatened By a Nightingale (1924). However, similar to the real world, the world of art was not going to imprison Max, he refused to adhere by it’s processes, in 1924, he sold his entire output, turned his back on his fawning admirers and departed for Indo-China. During his absence, Andre Breton published his First Surrealist Manifesto (1924), which established the role of the unconscious in art, in very similar terms to which Ernst had being thinking, indeed Max became one of the principal influences of the Surrealist movement. But he did not take the bait, he refused to be dragged into any movement, remaining solitary. He demanded that his imagination remain unfettered and so he strayed from genres and indeed from actual traditional processes, which he castigated for being too slow, too laborious. Instead he sought methods which offered spontaneity such as frottage and grattage.

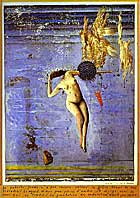

Perhaps it was such freedom from general consensus that allowed him to create his great series of premonitory works - Fishbone Forest (1927), Vision Induced by the Nocturnal Aspect of the Porte St. Denis (1927), Bird in a Forest (1927) and The Horde (1927). They harked back to the motifs of German Romanticism but they also launched into an apocalyptic future. Max had seen the world barbarically hack at itself before and he appeared to be predicting it occurring all over again. After warning of impending doom, Max withdrew once again into his head, creating his ‘private phantom’ Loplop, his hideous birdman alter ego who featured in his collage-novels, La Femme 100 têtes and Une Semaine de Bonté. He left it to Loplop to denounce the world’s future in his terribly disturbing The Angel of Hearth and Home (1937). It was painted in response to the triumph of fascism over Republican Spain, depicting the Angel of Death performing a war dance whilst the delighted Loplop applauds the stupidity of humanity’s tolerance. Seemingly exasperated he left Paris for idyllic Avignon, although tranquil is not a word that springs to mind when viewing the grotesque The Robing of the Bride (1940).

Fleeing the hell that was unleashing itself on Europe, the hell that he had predicted, Max shored up in New York in 1941. He embraced all that America had to offer, delighting in the syntax, culture and landscape. But the United States was to fare better from the exchange, as Ernst generously shared all his knowledge and vision of art with young, modernist painters. Ernst’s work was predominantly drawn from subjectivity, inspired from his personal experiences and it relied heavily on spontaneity with juxtapositions of material and imagery - two creative ideals which were to become staples of the Abstract Expressionist movement. Indeed, it was while in New York that Ernst created some small paintings by swinging a punctured can of paint above a canvas laid on the floor, something, which no doubt captivated a young Jackson Pollack.

Russell Shortt is a travel consultant with Exploring Ireland, the leading specialists in customised, private escorted tours, escorted coach tours and independent self drive tours of Ireland. Article source Russell Shortt, http://www.exploringireland.net/escorted-tours-page.html http://www.visitscotlandtours.com/tours/escorted-tours.html

|

|

Max Ernst - great German painter, sculptor, graphic artist, and poet. A prolific artist, Ernst is considered to be one of the primary pioneers of the Dada movement and Surrealism.

He was born on April 2, 1891, in Bruhl, Germany. He enrolled in the University at Bonn in 1909 to study philosophy, but soon abandoned this pursuit to concentrate on art. At this time he was interested in psychology and the art of the mentally ill. In 1911 Ernst became a friend of August Macke and joined the Rheinische Expressionisten group in Bonn. Ernst showed for the first time in 1912 at the Galerie Feldman in Cologne. At the Sonderbund exhibition of that year in Cologne he saw the work of Paul Cezanne, Edvard Munch, Pablo Picasso, and Vincent van Gogh. In 1913 he met Guillaume Apollinaire and Robert Delaunay and traveled to Paris. Ernst participated that same year in the Erste deutsche Herbstsalon. In 1914 he met Jean Arp, who was to become a lifelong friend.

Despite military service throughout World War I, Ernst was able to continue painting and to exhibit in Berlin at Der Sturm in 1916. He returned to Cologne in 1918. The next year he produced his first collages and founded the short-lived Cologne Dada [more] movement with Johannes Theodor Baargeld; they were joined by Arp and others. In 1921 Ernst exhibited for the first time in Paris, at the Galerie au Sans Pareil. He was involved in Surrealist activities in the early 1920s with Paul Eluard and Andre Breton. In 1925 Ernst executed his first frottages; a series of frottages was published in his book Histoire naturelle in 1926. He collaborated with Joan Miro on designs for Sergei Diaghilev that same year. The first of his collage-novels, La Femme 100 tetes, was published in 1929. The following year the artist collaborated with Salvador Dali and Luis Bunuel on their surrealistic film.

His first American show was held at the Julien Levy Gallery, New York, in 1932. In 1936 Ernst was represented in Fantastic Art, Dada, Surrealism at the Museum of Modern Art in New York. In 1939 he was interned in France as an enemy alien. Two years later Ernst fled to the United States with Peggy Guggenheim, whom he married early in 1942. After their divorce he married Dorothea Tanning and in 1953 resettled in France. Ernst received the Grand Prize for painting at the Venice Biennale in 1954, and in 1975 the Solomon R. Guggenheim Museum gave him a major retrospective, which traveled in modified form to the Musee National d'Art Moderne, Paris, in 1975. He died on April 1, 1976, in Paris. |